Beyond GDPR: 5 Surprising Truths About India’s New Data Privacy Act

After nearly a decade of deliberation, including seven years of development and five different drafts, India has now fully operationalized its first comprehensive data protection law, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), 2023. This is a pivotal and consciously chosen legislative moment for a country with an expanding digital economy and over 750 million internet users. The Act establishes a complete framework for how organizations must handle the personal data of Indian residents, marking a new era of digital governance.

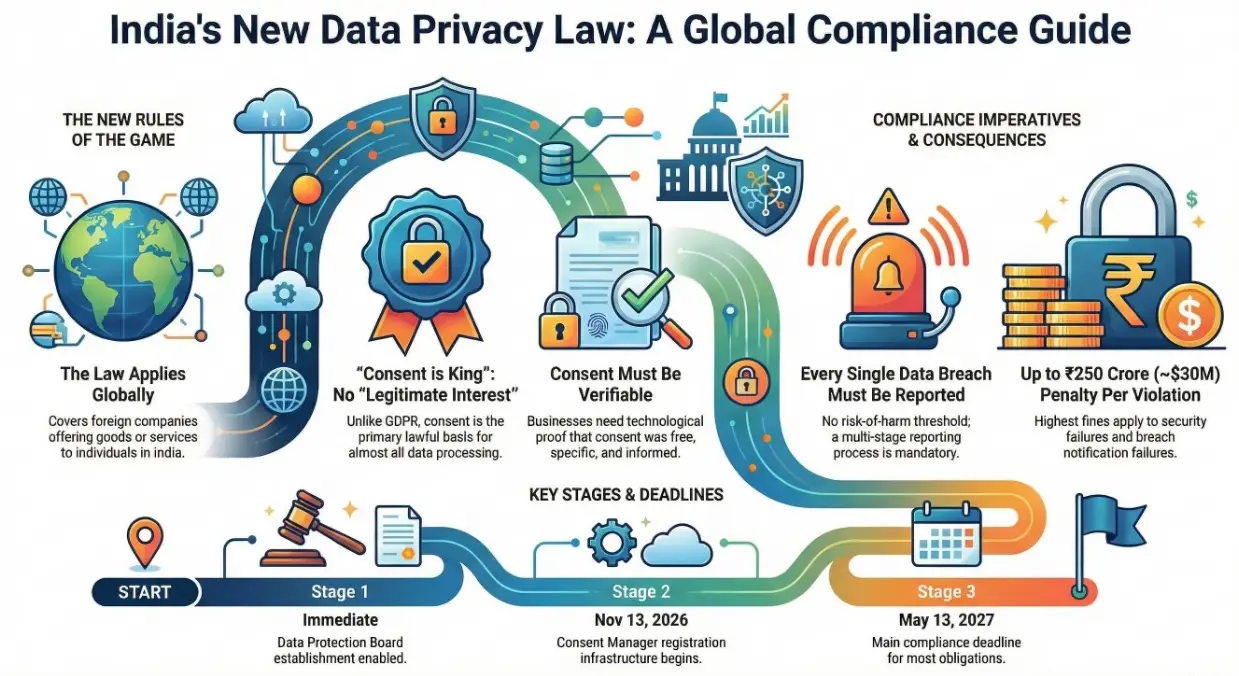

While many global businesses might assume the DPDPA is simply another version of Europe's influential General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a closer look reveals a framework with a distinctly different philosophy. India's law contains several surprising and counter-intuitive provisions that diverge sharply from international norms. These differences will fundamentally change how businesses and individuals approach data privacy in the world's most populous nation. Here are the five most impactful truths hidden within India’s new data privacy act.

1. Forget "Legitimate Interest": In India, Consent Is King

The most significant departure from GDPR is the DPDPA's complete omission of "legitimate interest" as a legal basis for processing personal data. This is not a minor tweak; it's a fundamental re-architecting of data privacy principles.

Under GDPR, "legitimate interest" is a flexible and widely used foundation relied upon by the vast majority of companies doing business in the EU for everything from marketing to security. The DPDPA removes this option entirely.

The consequence is that under Indian law, consent is the primary lawful basis for nearly all data processing activities. This isn't just any consent; it must be "free, specific, informed, unconditional and unambiguous with a clear affirmative action." Crucially, the DPDPA mandates verifiable consent, meaning organizations must maintain technological proof of consent. This imposes a non-trivial technical and record-keeping burden that transforms compliance from a simple policy rewrite into a concrete operational challenge. Global privacy policies built on the bedrock of legitimate interests will require a fundamental redesign to operate legally in the Indian market.

2. Absolute Responsibility: Data Fiduciaries Can't Pass the Buck

The DPDPA places an absolute, non-delegable responsibility on the "Data Fiduciary"—the entity equivalent to a "controller" under GDPR. The law makes this accountability ironclad with a critical phrase in Section 8(1), stating that a Data Fiduciary is responsible for compliance "irrespective of any agreement to the contrary".

This clause has profound implications. It prevents a Data Fiduciary from contractually shifting its legal liability for a data breach to its data processors. This is a stricter stance than GDPR's model; under Article 82(3) of the GDPR, a controller has a potential defense if it can prove it "is not in any way responsible for the event giving rise to the damage." The DPDPA's language removes this defense entirely, making the Data Fiduciary's liability truly inescapable in India.

This absolute responsibility also holds true even if a "Data Principal" (the user) fails to perform their own duties under the Act, such as providing authentic information. The law effectively removes any defense of contributory negligence, creating an accountability framework that places the full burden of protection on the organization that determines the purpose and means of processing data.

3. Report Every Single Breach—No Exceptions

Unlike GDPR, India's DPDPA does not have a risk-based threshold for breach reporting. This seemingly small detail creates a massive operational shift for compliance teams.

Under the DPDPA, a Data Fiduciary must notify the Data Protection Board of India (DPBI) and every affected individual in the event of any personal data breach. There is no exception for incidents that are minor or pose no real harm (e.g., an internal email containing a single customer's name and email address being accidentally sent to the wrong employee).

This stands in stark contrast to the GDPR framework, which only requires notification to authorities if a breach occurs and exempts notification to individuals if the incident is "unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons". The Indian approach prioritizes absolute state awareness and total transparency over the operational pragmatism favored by Western risk-based models, creating a significant compliance burden for companies.

4. Fines Go to the State, Not to the People

The DPDPA introduces a hefty penalty structure, with fines that can go as high as ₹250 crore (approximately $30 million) for a single violation, such as failing to implement reasonable security safeguards. However, what happens to this money is one of the law's most counter-intuitive features.

The DPDPA contains no provision for paying financial compensation to the individuals whose data was compromised. All monetary penalties collected for non-compliance are credited directly to the Consolidated Fund of India.

This represents a significant departure from India's previous IT Act framework, which allowed for data subject compensation. This model positions data breaches as an offense against the state's regulatory order rather than a private harm to be compensated. While affected citizens are not left without recourse, they are pushed toward seeking civil remedies in tort law—a significant procedural shift that designs the data protection law itself as a tool for state enforcement, not personal restitution.

5. Your Digital Legacy: The Unique "Right to Nominate"

In a forward-thinking move, the DPDPA introduces a unique "Right to Nominate" under Section 14 of the Act. This is a novel concept not found in major global privacy frameworks.

The right allows an individual (a Data Principal) to appoint another person to exercise their data rights—such as correction, updating, and erasure—on their behalf in the event of their death or incapacity.

This provision is particularly interesting when compared to GDPR, which applies only to living individuals. By creating a legal mechanism to manage a person's digital affairs posthumously, the DPDPA acknowledges the growing importance of our digital legacy in an increasingly online world and provides a clear process for handling it.

Conclusion: A Distinctly Indian Approach to Privacy

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act is far more than a "GDPR-lite" framework. It is a unique law built on a distinct philosophy that emphasizes absolute consent, ultimate fiduciary accountability, and state-centric enforcement. By removing legitimate interest, mandating the reporting of every breach, and creating an absolute liability model, India has charted its own course on data protection. These provisions create a new and challenging compliance landscape for global organizations and signal a different balance between individual rights, corporate responsibility, and state authority.

As India forges its own path on data protection, will this citizen-centric but state-enforced model become a new global standard, or will its practical challenges force a shift closer to existing international norms?