Policy Briefing: The Evolution and Current Landscape of Censorship and Information Control in Canada

1.0 Introduction: From State Censors to Digital Gatekeepers

The concept of censorship in Canada has evolved dramatically from the era of direct state control over print and film to a complex, multi-layered system of legal, regulatory, and technological information control. Where government censors once excised scenes from movies to protect public morals, the contemporary landscape is now shaped by a confluence of judicial rulings on expression, human rights tribunals adjudicating hate speech, national security agencies countering foreign interference, and powerful digital platforms moderating content for billions of users. This briefing will trace this evolution to provide professionals with a comprehensive understanding of the forces shaping the control of information in Canada today, from historical precedents rooted in protecting national sentiment to modern challenges of national security, data privacy, and the legislative rush to regulate the internet. This analysis begins with an examination of the historical foundations that first established the state's role in controlling information.

2.0 The Era of State-Led Censorship: Protecting Public Morals and National Sentiment (Early 20th Century - 1980s)

In the early- to mid-20th century, censorship in Canada was a strong, state-centric practice. The primary justifications for information control were the protection of the community from perceived social degradation, the promotion of a specific pro-British national character, and the management of information and dissent during wartime. This period established the legal and cultural precedents for state intervention in the public dissemination of ideas, media, and art.

The mechanisms and justifications for this era of censorship were multifaceted:

- Wartime and Political Censorship: During World War I, the federal government used the War Measures Act to impose strict censorship, banning over 250 publications, including many from the United States, to control the flow of news. In 1937, Quebec's Duplessis government passed the Act to protect the Province Against Communistic Propaganda, commonly known as the "Padlock Law," which banned the printing and distribution of any material deemed to be "propagating Communism or Bolshevism." This law was used to suppress political dissent for two decades until it was struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1957.

- The Rise of Provincial Film Censor Boards: Beginning in the early 1910s, provinces established their own censor boards to regulate the rising popularity of motion pictures. The Ontario board, formed in 1911, often acted as the primary censor, with other provinces making additional edits to theatrical prints to meet their local standards. In the 1920s, these boards objected to a wide range of content, often to promote a specific sense of Canadian nationalism and public morality.

Content Category Banned or Censored (1920s) | Rationale |

Disrespect for officers of the law | To maintain social order and respect for authority. |

Depiction and patriotic waving of the American flag | To promote a pro-British sentiment and Canadian nationalism. |

Scenes with women smoking | Considered improper and a negative moral influence. |

Nudity and illicit sexual relations | To protect public decency and community morals. |

Actors pointing guns at the camera | Concern over negative effects on children and "mentally weaker individuals." |

- The "Hicklin Test" and Community Standards: The early standard for censorship, particularly for film, was the "Hicklin test," which determined obscenity based on whether material had a tendency to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences. Over time, this rigid standard gradually gave way to judicial appeals to "community standards" as the ultimate determinant of what could be legally published or broadcast, setting the stage for future legal battles over freedom of expression.

This state-led model of censorship began to face significant challenges with the introduction of a new constitutional framework.

3.0 The Charter Era and New Battlegrounds for Expression (1980s - 2000s)

The enactment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 marked a pivotal shift in the landscape of Canadian censorship. By constitutionally protecting "freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression," the Charter provided a new and powerful basis for challenging state censorship. The reliance on nebulous "community standards" that defined the film censorship era evolved into direct legal tests for obscenity and hate speech. Consequently, conflicts over the limits of expression moved from the censor's office into the courts and human rights tribunals, with significant legal battles fought over queer art and literature, child pornography, and the definition of hate speech.

3.1 Obscenity, Art, and Censorship at the Border

The Charter era triggered a systemic conflict where pre-Charter "obscenity" standards, enforced by state bodies like Canada Customs, repeatedly clashed with emerging expressions of identity—particularly queer identity—that were newly protected. These were not isolated incidents but a sustained legal and cultural struggle.

- A landmark case was Little Sisters Book and Art Emporium v Canada. The Vancouver-based LGBT bookstore faced frequent confiscations of material by Canada Customs. In 2000, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that while Customs' legislative goal of preventing obscene materials from entering the country was valid, its practices were fundamentally flawed and discriminatory in application. The Court limited Canada Customs' authority, permitting it to confiscate only material that had been specifically ruled by the courts to be an offence under the Criminal Code.

- The lesbian art collective Kiss & Tell had their work censored by border officers on four separate occasions. Their Drawing the Line photographs, which represented lesbian sexuality, were confiscated, as were magazines and postcard books featuring the images. Despite their work being shown in Canadian galleries, copies were repeatedly detained at the border while being shipped into the country.

- In 1993, police raided the Mercer Union Gallery in Toronto and confiscated paintings and drawings by artist Eli Langer. The art, which depicted fictional children in sexual acts, led to Langer and the gallery director being charged under newly enacted child pornography laws. The charges were later withdrawn, but the case sparked a national debate on artistic freedom. This occurred in the context of the Supreme Court's R v Butler (1992) ruling, which held that obscene pornography was not protected expression, and was followed by the R v Sharpe (2001) decision, which upheld the criminalization of possessing fictional child pornography.

3.2 Hate Speech and Human Rights Law

The Charter era also saw human rights law become a key battleground for regulating expression.

- Section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act formerly prohibited the communication of hate messages by telecommunication, which included content on the internet. A statement was deemed hateful if it was "likely to expose a person or persons to 'hatred or contempt'" based on a prohibited ground of discrimination, such as religion or sexual orientation.

- High-profile cases in the mid-2000s fueled a national debate over the role of human rights commissions in policing speech. Complaints were filed against publisher Ezra Levant for publishing the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons and against Maclean's magazine and author Mark Steyn over an article about Islam.

- These controversies, cited as a motivating factor by critics who argued Section 13 was being used to chill freedom of expression, ultimately led to its repeal by Parliament in 2013.

These legal frameworks, designed for a pre-digital world, soon contended with the emerging complexities of the internet.

4.0 The Digital Age: New Frontiers of Information Control

The internet has fundamentally decentralized information control, shifting power from state censors to a complex new ecosystem of private platforms, data brokers, and national security agencies, each with distinct and often conflicting governance imperatives. The modern challenge is no longer just about what content the state permits, but about who controls the vast troves of personal data that define our digital lives and how to counter sophisticated threats that exploit the open nature of the online world.

4.1 Data Privacy as a Form of Information Governance

Canada's foundational federal privacy law for the private sector is the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). These principles collectively create a framework of "information rights," establishing the individual as the primary controller of their data—a stark contrast to the earlier state-centric model of information control.

PIPEDA is structured around ten core principles:

- Accountability: An organization must appoint a privacy officer and be responsible for the personal information it controls.

- Identifying Purposes: The purposes for collecting personal information must be identified before or at the time of collection.

- Consent: An individual's informed permission is required for the collection, use, or disclosure of their personal information.

- Limiting Collection: Collection must be limited to information that is necessary for the identified purposes.

- Limiting Use, Disclosure, and Retention: Information must only be used for its intended purpose and kept only as long as necessary.

- Accuracy: Personal information must be as accurate, complete, and up-to-date as necessary.

- Safeguards: Information must be protected with appropriate security measures against loss or theft.

- Openness: Policies and practices regarding the management of personal information must be clear and readily available to the public.

- Individual Access: Individuals have the right to access and challenge the accuracy of their personal information held by an organization.

- Challenging Compliance: Organizations must have procedures to address complaints about their compliance with these principles.

Under PIPEDA, organizations also have mandatory breach notification requirements. They must report any breach of security safeguards to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) and notify affected individuals if the breach poses a "real risk of significant harm" (RROSH). "Significant harm" is explicitly defined to include "bodily harm, humiliation, damage to reputation or relationships, loss of employment... financial loss, identity theft," among other injuries. Records of all breaches must be maintained for at least 24 months.

4.2 National Security and the Information Environment

The modern national security environment has evolved to include pervasive and sophisticated cyber threats framed within a broader geopolitical rivalry. State-sponsored cyber operations, foreign interference, and disinformation campaigns have become primary concerns for agencies like the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security.

Hostile state actors persistently target Canada's government, private sector, and diaspora communities. The primary state adversaries and their corresponding cyber threat activities are outlined below:

Primary State Adversary | Associated Cyber Threat Activities |

People's Republic of China (PRC) | Espionage, intellectual property (IP) theft, and malign influence integral to its goal of challenging U.S. dominance. Includes transnational repression to silence activists and diaspora groups. |

Russian Federation | Espionage, disinformation, and disruptive cyber operations targeting government and critical infrastructure as part of a strategy to "confront and destabilize Canada and our allies." |

Islamic Republic of Iran | Coercion, harassment, and repression of opponents abroad, including dissidents in Canada, often through cyber surveillance and social engineering campaigns. |

Republic of India | Espionage targeting Government of Canada networks and transnational repression to influence diaspora communities and silence critics of the government. |

Islamic Republic of Pakistan | Foreign interference in democratic processes and transnational repression targeting diaspora communities and critics in Canada to counter perceived "anti-Pakistan" sentiment. |

Emerging technologies, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), are amplifying these threats. State and non-state actors are using generative AI to create "realistic deepfakes" and "craft personalized phishing emails at a scale previously unimaginable," enhancing the quality and persuasiveness of social engineering attacks and disinformation campaigns. This creates a strong rationale for enhanced government monitoring and potential regulation of the digital space.

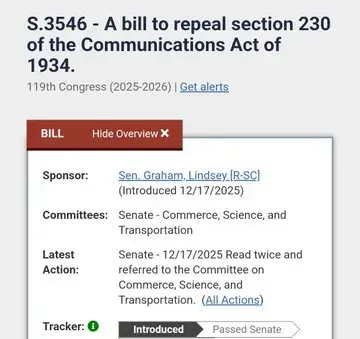

4.3 The Legislative Rush to Regulate the Internet

In recent years, the federal government has introduced a series of legislative initiatives aimed at regulating online content and the digital platforms that host it. These bills have sparked significant controversy and debate over their potential impact on freedom of expression and access to information.

- Online Streaming Act (Bill C-11): This act gives the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) the power to regulate digital media platforms as "broadcasters," a digital-era evolution of the same impulse that created the provincial film censor boards. The purpose is to require platforms to contribute to Canadian content. The legislation has been controversial due to concerns that its broad language could be applied to regulate user-generated content.

- Online News Act (Bill C-18): Intended to force large digital platforms to compensate Canadian news organizations for content, this legislative intervention triggered a predictable market response from Meta, which chose to withdraw from the news market rather than submit to the regulatory framework. This resulted in a net reduction of news access for Canadian users on its platforms.

- Proposed Online Harms Act (Bill C-63, formerly C-36): An initial proposal (Bill C-36) to tackle online hate speech did not pass. A subsequent advisory group's broader recommendations for a Digital Safety Commissioner to regulate a range of harmful content led the government to postpone a redrafted version amidst accusations of potential overreach and censorship.

Other legislative efforts, such as Bill S-210 (which proposes mandatory age verification systems for websites with sexually explicit material), further illustrate the broadening scope of attempts to regulate the Canadian internet. These overlapping challenges define the current policy environment.

5.0 Contemporary Issues and Future Outlook

The contemporary landscape of information control in Canada is defined by a critical and ongoing effort to balance foundational rights, such as freedom of expression, with the need to address emerging digital threats. This balancing act is playing out in public inquiries, in the policies of private technology companies, and in a continuous cycle of legislative reform, highlighting an ongoing debate about the appropriate roles of government, private platforms, and the judiciary in the digital age.

5.1 The Modern Balancing Act: Expression vs. Security

The core tension in Canada's modern information ecosystem lies between protecting freedom of expression and the necessity of countering sophisticated foreign interference. The Public Inquiry into Foreign Interference (PIFI) exemplifies this challenge. The inquiry has revealed the central dilemma of modern intelligence work: CSIS’s mandate is to gather intelligence covertly, but effectively countering foreign interference requires making that intelligence public and actionable, creating an inherent conflict between the secrecy required for operations and the transparency needed for democratic resilience.

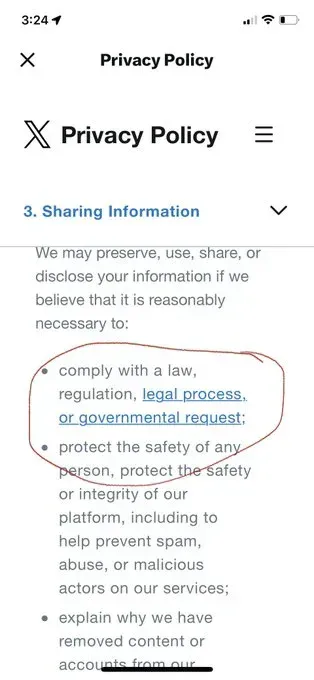

This balance is further complicated by the powerful role of private sector content moderation. Platform policies have a profound impact on the public information sphere, often independent of government regulation. For example, Meta's announcement on January 8, 2025, that it would move away from relying on third-party fact-checkers in favor of a "community notes" model represents a significant shift in content moderation philosophy. This decision, which emphasizes a particular vision of freedom of expression, will reshape how information is vetted for billions of users and illustrates the immense power platforms wield in controlling the digital discourse.

5.2 The Evolving Legal and Regulatory Horizon

Canada's legal framework for data and information is in a state of continuous evolution. The rules are far from settled, primarily because Canada is struggling to reconcile its traditional rights-based legal framework, exemplified by the Charter, with the borderless, fast-moving, and often anonymous nature of digital threats—a problem legacy legislation was never designed to solve.

Key legislative proposals are set to reshape the landscape. The federal government's Bill C-27, currently before Parliament, aims to replace PIPEDA with a new consumer privacy protection act, introducing significantly enhanced enforcement powers. The proposed fines—up to 5% of a company's global revenue—are significantly higher than those in Québec's privacy law, which carry penalties of up to 4%, highlighting the escalating seriousness with which Canadian jurisdictions are treating privacy violations. At the provincial level, similar reforms are underway, including Alberta's review of its Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA). This continuous cycle of reform indicates that the rules governing data, privacy, and online content will remain a central policy focus.

6.0 Conclusion: Navigating Canada's Complex Information Ecosystem

The control of information in Canada has journeyed from a system of direct state censorship, focused on public morals and national sentiment, to a complex and decentralized ecosystem where control is exerted by a diverse array of actors. The battlegrounds have shifted from the film censor's office to the nation's highest courts, regulatory tribunals, national security agencies, and the opaque content moderation departments of powerful digital platforms. We assess that the central challenge for Canadian policymakers in the years ahead will be to develop a coherent and balanced framework that mitigates genuine harm and counters sophisticated security threats without unduly infringing on the fundamental freedoms of expression and privacy that underpin Canadian democracy. Navigating this new environment will require careful, considered, and adaptable governance that can keep pace with technology while remaining true to the nation's core values.