Briefing Document: The 50-Year Trajectory of U.S. Privacy Law and the Imperative for a New Social Movement

Executive Summary

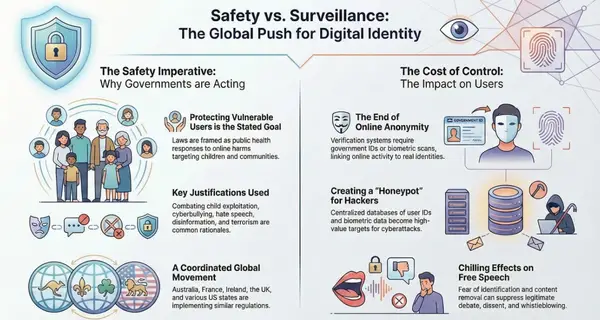

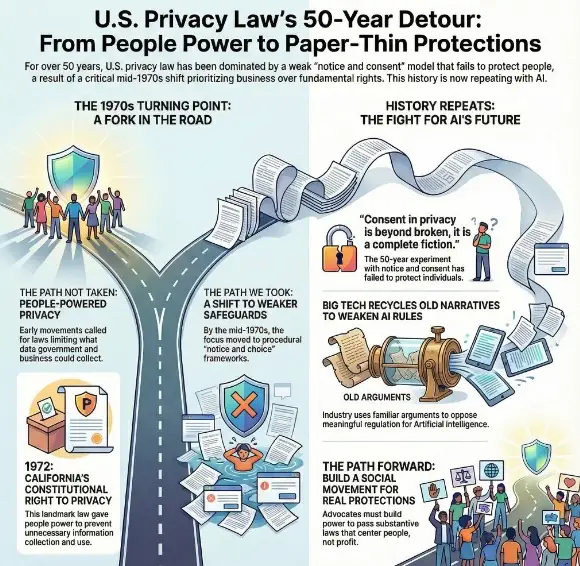

For more than five decades, the United States' approach to privacy law has fundamentally failed to protect people and democracy, instead prioritizing corporate profit and government surveillance. This failure stems from a pivotal historical shift in the mid-1970s, when a promising movement toward robust, substantive privacy protections was deliberately undermined and replaced by a weak procedural framework of "notice and choice." This framework, which places an impossible burden on individuals, has proven disastrously inadequate against the power of modern technology.

The high-water mark for U.S. privacy was the 1972 passage of the California constitutional right to privacy—the last truly comprehensive privacy law enacted in the nation. It was designed to give people power over how technology impacts their lives. However, this trajectory was derailed by a confluence of political, academic, and industrial forces, notably the "War on Drugs," which fueled a surveillance state; the influential academic work of Alan Westin, who championed a "balanced" approach favoring data collection; and the policy outcomes steered by Willis Ware through federal committees, which resulted in a toothless, government-only Privacy Act of 1974.

Today, as artificial intelligence (AI) accelerates technological change, history is repeating itself. Industry is recycling the same narratives to oppose meaningful regulation. To secure a future where technology serves justice and equity, it is imperative to build a powerful and intersectional social movement. While the public interest community has made progress in building relationships and executing strategic campaigns, it remains critically weak in developing a compelling narrative to counter industry propaganda and lacks the sustainable structures needed to build enduring power. This document synthesizes the historical analysis of this failure and outlines the strategic path forward.

1. The Enduring Failure of Contemporary U.S. Privacy Law

The current landscape of U.S. privacy law is defined by its inadequacy. For 50 years, it has been locked in a flawed experiment relying on weak procedural safeguards that are likened to "bringing a pocketknife to the fight, when the other side has a fully loaded tank."

- The Flawed "Notice and Choice" Paradigm: The dominant legal framework is based on notice and consent, a model derided as creating "wet napkin privacy laws." This approach places an impossible burden on individuals to manage their own privacy against powerful corporate and government entities.

- Consent in the digital age is described as "beyond broken, it is a complete fiction," leading to "unwitting and coerced consent."

- This model disproportionately fails marginalized communities, who are often forced to engage with intrusive systems due to structural power dynamics and face compounding vulnerabilities from discriminatory surveillance.

- Outdated Federal Legislation: Key federal laws are decades old and riddled with loopholes.

- The Privacy Act of 1974: Intended to protect against government data abuse, it was inadequate upon enactment and contains "soft spots" like the "routine use" exception.

- The Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA): The primary law limiting government surveillance of electronic communications has not been meaningfully updated since 1986, an era before the World Wide Web.

- High Costs to People and Democracy: The absence of substantive limits on data collection has incurred severe costs.

- Government Surveillance: Technology is used to fuel immigration deportations, racist policing systems, and the tracking of activists.

- Corporate Sector: Surveillance business models and biased algorithms are allowed to prioritize profit over public health, safety, and democratic integrity.

2. A Lost Opportunity: The Push for Substantive Privacy (Late 1960s–Early 1970s)

At the dawn of the modern computer age, there was significant political and social energy directed toward establishing robust, substantive privacy laws that would grant people genuine power over technology.

- Early Calls for Substantive Limits: As early as 1967, legal experts and civil society leaders recognized that computerization demanded bold action.

- Figures like Arthur Miller argued for a "total and complete revamping of our legislative approach," stressing the need for "controls on input" and asserting that for certain sensitive data, "we just shouldn’t collect it—period!"

- ACLU Executive Director John Pemberton cautioned in 1968 that legislation must "discriminate about the kinds of information that are gathered and stored."

- Intersectional Movement Support: Support for strong privacy protections came from a broad coalition.

- Social Movements: Activist groups, who were targets of government surveillance programs like the FBI's COINTELPRO, understood the threat of technology. The Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Plan explicitly included a demand for "people’s community control of modern technology."

- Elite Support: Privacy concerns also resonated with wealthy individuals who resented government intrusion into their financial affairs, creating a diverse, if temporary, alliance.

- The High-Water Mark: 1972 California Constitutional Right to Privacy: This political momentum culminated in the passage of a landmark privacy amendment in California.

- It is the last truly comprehensive privacy law passed in the U.S., protecting against invasions by both government and business and covering both informational and autonomy privacy.

- Its "moving force" was the concern over "accelerating encroachment on personal freedom and security caused by increased surveillance and data collection."

- Critically, it established privacy as a "fundamental and compelling interest" that could be "abridged only when there is compelling public need," placing the burden of justification on the intruder.

3. The Mid-1970s Pivot: How U.S. Privacy Law Was Derailed

The powerful, people-centric vision of the 1972 California law was never replicated at the federal level. A pivotal turn in the mid-1970s shifted the national narrative away from substantive rights and toward accommodating information collection, government surveillance, and corporate profit. This derailment was driven by three primary factors, referred to as the "Three W's."

- The War on Drugs: The political backlash to the civil rights movement was reframed as a "law and order" agenda. This movement fueled punitive policies, massively expanded policing and surveillance, and created a political climate hostile to privacy rights. This shift also led to a more conservative judiciary, which ultimately weakened the California constitutional right to privacy in the 1994 Hill v. NCAA decision by subverting its compelling interest standard and creating a difficult new test for plaintiffs.

- Alan Westin: Described as the "father of modern privacy law," Westin's influential 1972 report, Databanks in a Free Society, was instrumental in shifting the paradigm. He promoted a "balanced" framework that accepted widespread data collection as a "need" for society and advocated for procedural safeguards rather than substantive limits. This approach characterized public fears as "confused thinking" and "wild and misinformed testimony," helping to sideline more robust protections and entrench the notice-and-consent model that dominates today.

- Willis Ware: As a RAND Corporation engineer and chair of key federal committees, Ware played a significant role in shaping policy.

- The HEW Committee (1972-1973): As chair, Ware steered this diverse committee toward adopting the Fair Information Principles (FIPs), a "safeguards" approach that focused on transparency and fairness but did not fundamentally challenge the "collect it all" ethos. The committee intended FIPs to apply comprehensively to both government and business.

- The Privacy Act of 1974: A political "compromise" between Congress and the Ford administration resulted in a law that applied the FIPs framework only to government agencies, kicking the can on private-sector regulation.

- The Privacy Protection Study Commission (PPSC) (1977): Ware served as vice-chair of this subsequent, far less diverse, and more business-oriented commission. Its final report elevated corporate costs as the "most compelling competing interest," favored self-regulation, and failed to recommend any meaningful private-sector privacy protections, effectively stalling federal progress.

4. The Path Forward: Building a Social Movement for the AI Age

To avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, the public interest community must build a durable social movement capable of challenging entrenched power and enacting substantive laws for the AI age. This requires strengthening core movement-building blocks.

Areas of Growth: Relationship, Strategy, and Action

In the last decade, the public interest technology community has made significant progress in key areas, exemplified by the successful campaign against government use of face surveillance.

- Relationships: There has been marked growth in building cross-issue and cross-level coalitions. The face surveillance campaign mobilized a diverse coalition of over 85 racial justice, faith, civil rights, and immigrant rights groups.

- Strategy and Action: The community has effectively deployed integrated advocacy, using a layered approach of legislative work, corporate advocacy, litigation, organizing, and communications. This has led to tangible victories, including dozens of local bans on facial surveillance, state-level limits, and moratoriums on sales from major tech companies like Amazon and Microsoft.

Critical Weaknesses: Narrative and Structures

Despite progress, the movement is hampered by critical weaknesses that prevent it from building the power necessary for systemic change.

- Narrative: The "Woefully Weak" Link: The public interest community has consistently failed to develop and maintain a powerful, disciplined narrative. It is routinely outmaneuvered by pervasive government and industry narratives designed to undermine regulation and instill a sense of powerlessness.

Industry Narrative | Description |

1. Good for the World | The claim that what is good for technology companies is inherently good for society, and that any regulation will harm people. |

2. Resistors are "Luddites" | The characterization of anyone who challenges technology or calls for regulation as backward-thinking and anti-innovation. |

3. Technology is Inevitable | The assertion that technological advancement is an unstoppable force ("the genie is out of the bottle"), making resistance futile and promoting submission over participation. |

4. Technology is Too Complicated | The argument that technology issues are too complex for the public and policymakers to understand, a tactic termed "AI-washing" used to intimidate and silence critics. |

5. Technology is a Neutral Tool | A defensive pivot claiming that technology companies are not responsible for how their products are used, deflecting accountability for harmful applications. |

- Structures: The Need for Sustainability: The movement requires more sustainable structures and resources.

- There is a need for consistent funding and training to support sustained collaboration, especially for grassroots organizations.

- Academic institutions must expand cross-disciplinary curricula in law, public policy, and computer science to train a new generation of leaders skilled in integrated advocacy and capable of addressing the complex challenges of the AI age.

5. Key Quotations

"The social justice community lost the fight for robust, substantive privacy law in the mid-1970s and has never been able to rebuild the power necessary to get privacy law back on track."

"People and democracy are paying the price for a United States vision of privacy law that has been clouded for more than 50 years by powerful efforts intended to utilize new technology to perpetuate political, economic, and social power structures, not support greater access, equity, and justice."

"Now history is replaying. Like during debates about early computerization in the 1970s, business interests are recycling the same narratives about AI and how it will be used to benefit ‘all of society’ while opposing any substantive regulation."

"It is recognized that consent in privacy is beyond broken, it is a complete fiction."

"The public interest community needs to counter the industry’s AI-washing, tech exceptionalism narrative with a strong spin cycle that centers the needs of people and society."